Money-saving tips have officially become problematic. The cost of living crisis is shining a harsh light on some of the biggest, most frayed holes in our social safety net. So, it’s not surprising that certain politicians have been lambasted for advising the public to trade down to value products, cook more and get a second job.

Anyone who pretends your average consumer can overcome energy bills of nearly £3,000 and worldwide food shortages through savviness alone is either deluded, callous or both. That’s why Rishi Sunak has agreed, against all his political instincts, to spend an extra £15bn to convert his £200 energy loan into a £400 grant and send emergency payments of £650 to poorer households.

Tory MPs will be far more reluctant to offer up their startingly original money-saving strategies when their own Chancellor has conceded they aren’t enough. Still, spare a thought for financial journalists who are being asked to do the increasingly impossible: provide advice that doesn’t come across as out of touch, judgemental and patronising.

There’s growing public hostility to even the most well-intentioned and useful suggestions. One producer told me just before a pre-recorded radio interview that their young audience feedback on money-saving tips has become far more negative recently (before asking me to deliver my best money-saving tips. No pressure!)

It’s partly because the scales are dropping from our eyes about today’s online hustle culture. Influencers, entrepreneurs and so-called “girl boss” feminists might have previously persuaded us that individual effort can always triumph over adverse circumstances without any loss of integrity or authenticity.

Now, we’re not so sure. And that objectivity has extended to money-saving. We’re slowly realising it’s all a bit more complicated than the clickbait articles and 60-second “how to” videos would have us believe.

More from Saving and Banking

Take food shopping, the most obvious place to start cutting back. Experts rightly preach the benefits of cooking meals at home, being resourceful with ingredients and shunning expensive takeaways. All of this is self-evident if you’re of an older vintage, having grown up with finite food choice and simple meals (probably cooked by a stay-at-home mum) every night.

But achieving the maximum food savings today requires that most of us make radical lifestyle changes. I am largely in control of my hours with no dependents or caring responsibilities. But a working life still means I don’t always have the time and energy for the demands of food frugality.

Batch cooking, meal planning, comparison shopping, getting to the clearance shelves at the right time…it can all become incredibly time-consuming, disruptive and exhausting for working families, as anti-poverty campaigner Jack Monroe has argued. Of course, poorer households have no choice. But the rest of us with a financial cushion make trade-offs so we’re not trapped in constant drudgery.

However, there’s another reason why money-saving advice can sometimes feel disconnected from reality. It assumes we are all homo economicus, the model put forward by John Stuart Mill in the 19th century to describe our infinite capacity to make rational decisions. Just stop doing this, start doing that, and hey presto, you’ll save money. Simple!

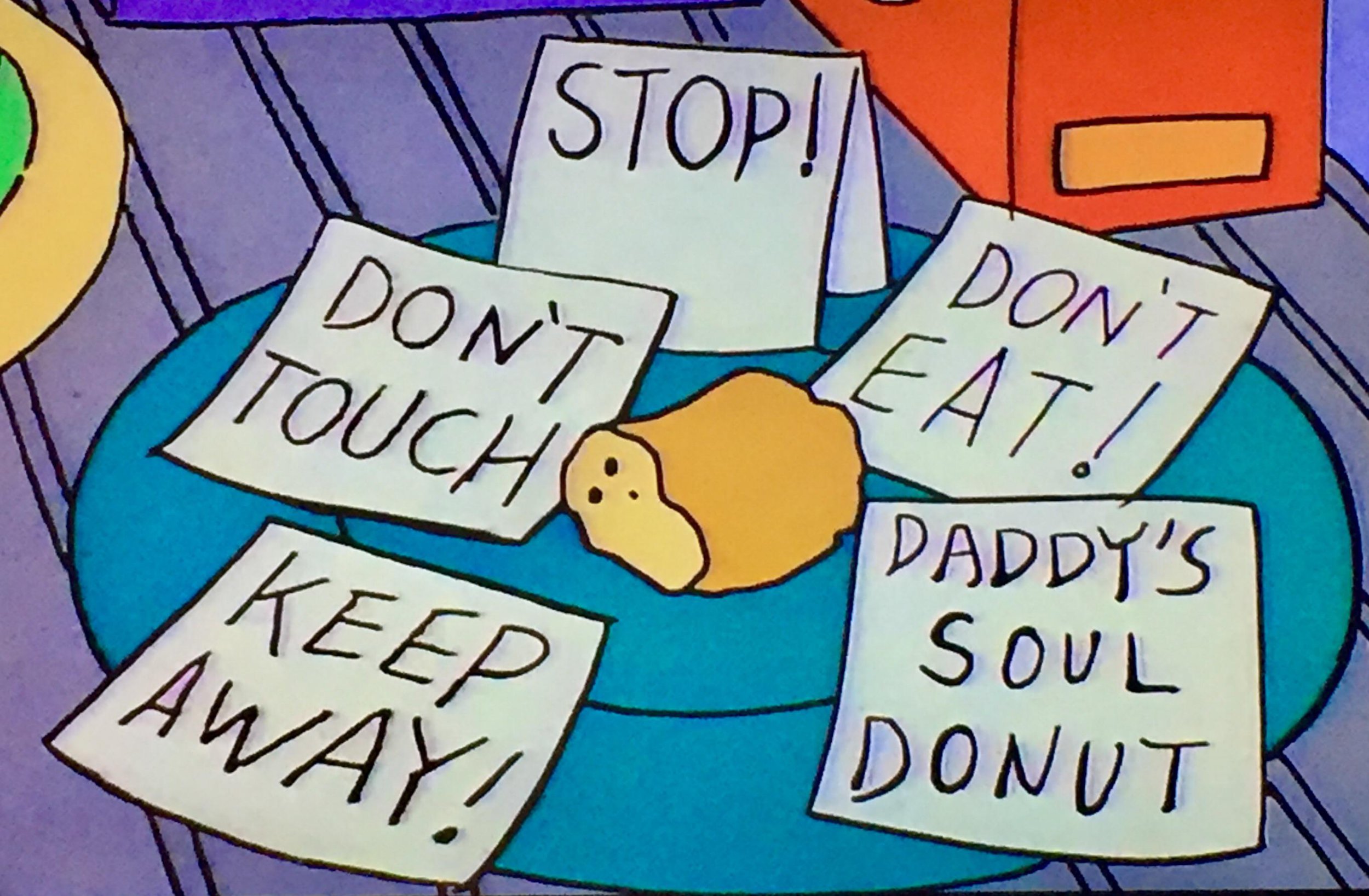

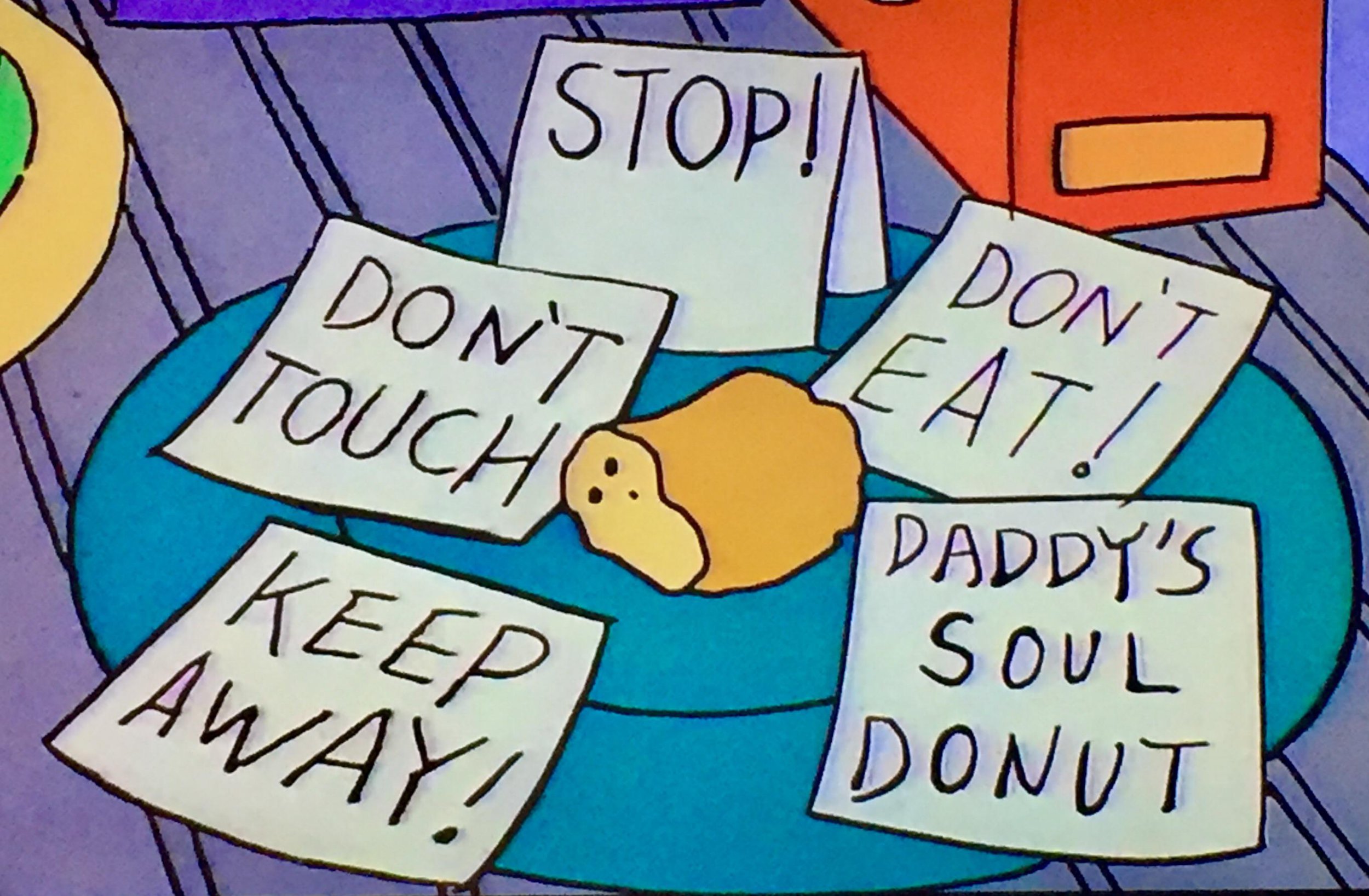

Except… we’re less homo economicus, more Homer Simpson (to borrow a joke from Philip Corr and Anke Plagnol). In their book, Behavioural Economics: The Basics, the two academics describe various experiences that will be familiar to all of us, no matter how rational we try to be.

There’s our misuse of commitment devices, like expensive gym memberships we don’t use despite our best intentions. There’s our inconsistent “mental accounting” whereby we might scrimp in one area while splashing out in another. And think about how much our spending is driven by psychological and physiological states (such as stress or hunger), which in turn can be heavily determined by our personality traits.

When Homer sells his soul to The Devil Flanders for a doughnut, we can all relate on some level. Just substitute the donut for whatever product has forged those instant, delicious reward pathways in your head. Because I guarantee you, there will be at least one. And breaking down those pathways once they start controlling you is the single hardest thing you can do. But it’s undoubtedly the most important.

That’s why I empathise with the students living in my building who use takeaway apps several times a week. These apps are addictive, normalised and relentlessly marketed. But it’s why those young people need deeper advice on how to end their reliance on takeaways, which will save them thousands of pounds in the long run. Simply telling them to stop won’t work.

None of us should give up trying to save money. But it’s time to acknowledge the often overwhelming internal and external forces that mean for many of us, money-saving is more in the breach than the observance.